The Effect Of Hydrogen In Steel

The presence of hydrogen causes general embrittlement in steel and during welding may lead directly to cracking of the weld zone. The following terms are forms of hydrogen related problems:

- hydrogen induced cold cracking (HICC),

- fissures/micro-fissures,

- chevron cracks,

- fish-eyes.

Mechanism

The following text describes the mechanism believed to be involved with the formation of hydrogen induced cold cracking (HICC) in steel:

Hydrogen enters a weld via the welding arc. The source of hydrogen may be from moisture in the atmosphere, contamination on the weld preparation, or moisture in the electrode flux. With the MMA and SAW processes, the selection of flux type will also affect the H₂ content.

The intense heat of the arc is enough to breakdown the molecular hydrogen (H₂) into its atomic form (H). Hydrogen atoms are the smallest atoms known to man and therefore can easily infiltrate amongst the iron atoms while the weld is still hot. When the weld area is hot, the iron atoms are more mobile thereby producing larger gaps between themselves, i.e. the steel is in an expanded condition.

As the weld cools down, most of the hydrogen diffuses outwards into the parent material and atmosphere, but some of the hydrogen atoms become trapped within the weld zone. This is due to the iron atoms settling as the weld cools, therefore the gaps between them become smaller, i.e. the steel is contracting.

Below 200°C, the element of hydrogen prefers to be in its molecular form (H₂), the individual atoms of hydrogen are attracted towards each other as the weld cools and they congregate in any convenient space as microscopic gas bubbles.

When the hydrogen molecules exist in large numbers, a lot of pressure is exerted – 60,000 to 200,000 PSI! Because of this internal pressure, the adjacent grain structure may react in one of two ways:

- It may deform slightly to reduce the pressure. This will occur if the surrounding metal is ductile, e.g. pearlite;

- It may separate completely to reduce the pressure, i.e. crack. This will occur if the surrounding metal is brittle, e.g. martensite.

Weld fractures associated with hydrogen are more likely to occur in the HAZ as this area tends to have increased brittleness. It must also be observed that it usually takes an external stress to initiate and propagate a crack. Lower temperatures will decrease the fracture toughness of the steel and at the same time increase H₂ pressure.

Conclusion:

Before hydrogen cracking occurs, the following criteria must exist:

Austenitic stainless steel (high chromium content) is not prone to hydrogen related cracking.

- Hydrogen;

- A grain structure susceptible to cracking normally means brittle but not necessarily; martensite grain structures, which are brittle, are very susceptible to cracking;

- Stress;

- A temperature 200°

To reduce the chance of hydrogen cracking:

- Ensure joint preparations are clean;

- Preheat the joint preparations;

- Use a low hydrogen welding process, or if using MMA, use hydrogen controlled electrodes;

- Use a multi-pass welding technique;

- Use H₂ release post-heat treatment.

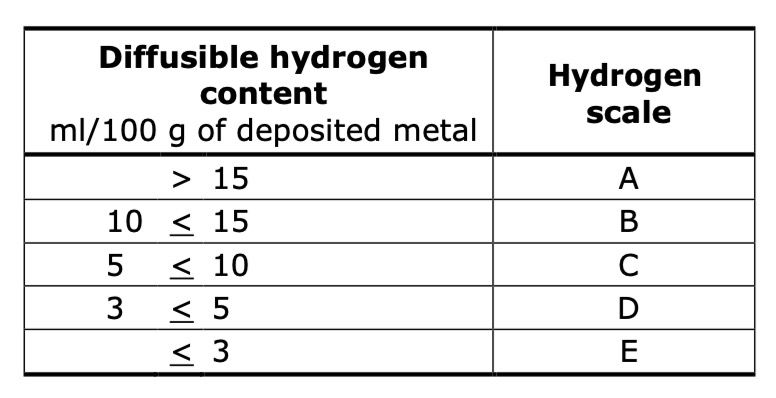

Hydrogen scales

The following chart shows terminology used by the International Institute of Welding (IIW) and BS EN 1011 Part 2 with regard to hydrogen levels per 100 grams of weld metal deposited:

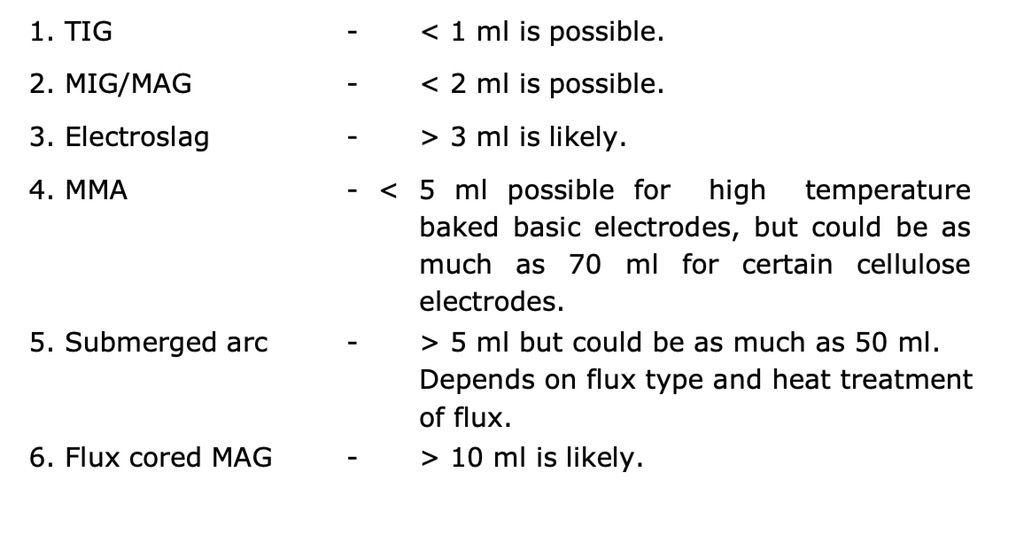

Hydrogen content of weld processes The hydrogen content in a specific weld depends on a variety of factors such as the degree of contamination on the weld preparation, the arc length used, the amount of water vapour in the immediate environment and cooling rate of the weld. However, it is still possible to approximate hydrogen contents of welds made under typical well controlled conditions. The amount of hydrogen remaining in a weld – assuming no hydrogen release post-heat treatment process has been used – will depend largely on the welding process used. Shown below are welding processes with hydrogen levels achieved per 100 grams of weld metal deposited